Alyki (near Thessaloniki) in northern Greece is rich in wildlife. The area was visited by an

ornithological student expedition from London University in 1979, who

discovered the large population of Hermann's tortoises and did a brief population study

(Stubbs, Espin & Mather, 1979). A return expedition in summer 1980 by myself, David Stubbs,

Elizabeth Pulford and Wendy Tyler was made specifically to study the tortoise population.

Work at Alyki began well with the site mapped and over 100 tortoises permanently marked by

notching the marginal scutes (Stubbs, Hailey, Pulford & Tyler,

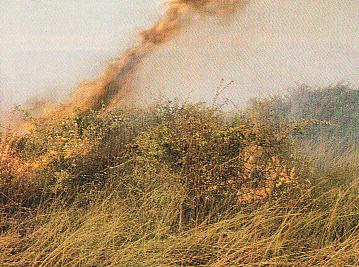

1984). Unknown to us, however, the site was the centre of a planning dispute between

the villagers of Kitros, who collectively owned the land, and the local authorities who

refused proposed industrial development of the area. Faced by further ecological work at the

site, the villagers responded by setting the heathland on fire to reduce its wildlife value,

then using a bulldozer and rotavator to flatten the site.

The expedition remained and marked over 800 tortoises in total, besides describing

the effect of fire and ploughing on tortoises and other wildlife. Analysis of the recapture

data suggested that there had been about 5000 tortoises on the main study area (called the

main heath) before the fire, with population densities of more than 100 tortoises ha-1

in the most favourable habitats

(Stubbs, Hailey, Tyler & Pulford, 1981). Another

expedition to Greece in summer 1982 by

myself, David Stubbs, Elizabeth Pulford and Jan Mata revisited Alyki and marked more than 1000

further tortoises, besides recapturing many marked in 1980.

Work at Alyki began well with the site mapped and over 100 tortoises permanently marked by

notching the marginal scutes (Stubbs, Hailey, Pulford & Tyler,

1984). Unknown to us, however, the site was the centre of a planning dispute between

the villagers of Kitros, who collectively owned the land, and the local authorities who

refused proposed industrial development of the area. Faced by further ecological work at the

site, the villagers responded by setting the heathland on fire to reduce its wildlife value,

then using a bulldozer and rotavator to flatten the site.

The expedition remained and marked over 800 tortoises in total, besides describing

the effect of fire and ploughing on tortoises and other wildlife. Analysis of the recapture

data suggested that there had been about 5000 tortoises on the main study area (called the

main heath) before the fire, with population densities of more than 100 tortoises ha-1

in the most favourable habitats

(Stubbs, Hailey, Tyler & Pulford, 1981). Another

expedition to Greece in summer 1982 by

myself, David Stubbs, Elizabeth Pulford and Jan Mata revisited Alyki and marked more than 1000

further tortoises, besides recapturing many marked in 1980.

David Stubbs also visited Alyki in spring 1983 during his work on

Testudo hermanni in France. The data from 1980,

1982 and 1983 allowed a better estimate of the effects of the fire and ploughing; we

estimated that these had killed about 40% of the tortoises. On the other hand, this meant that

60% had survived, which was remarkable given the severity of the fire and thoroughness of the

subsequent ploughing. Tortoises seem rather resistant to environmental catastrophes, at the

level of both the individual and the population

(Stubbs, Swingland, Hailey & Pulford, 1985).

Many tortoises captured in 1982 had been

badly injured by fire or plough, but showed substantial powers of recovery. A new carapace

develops beneath the original one, which eventually falls away. The white bony plates are all

that remain of the original carapace of the tortoise shown here, and these will be lost in time.

The regenerated carapace is less regular than the original.

David Stubbs also visited Alyki in spring 1983 during his work on

Testudo hermanni in France. The data from 1980,

1982 and 1983 allowed a better estimate of the effects of the fire and ploughing; we

estimated that these had killed about 40% of the tortoises. On the other hand, this meant that

60% had survived, which was remarkable given the severity of the fire and thoroughness of the

subsequent ploughing. Tortoises seem rather resistant to environmental catastrophes, at the

level of both the individual and the population

(Stubbs, Swingland, Hailey & Pulford, 1985).

Many tortoises captured in 1982 had been

badly injured by fire or plough, but showed substantial powers of recovery. A new carapace

develops beneath the original one, which eventually falls away. The white bony plates are all

that remain of the original carapace of the tortoise shown here, and these will be lost in time.

The regenerated carapace is less regular than the original.

It was apparent in 1980 that many more males than females were found at Alyki, which could

have been due to either greater activity of males (ths making them easier to find) or to a

real bias in the population sex ratio. Mark-recapture analysis (which takes account of

different activity and ease of finding) of the data from 1980, 1982 and 1983 showed that the

sex ratio was indeed biased, with about two males per female in the

main heath population (Stubbs et al., 1985). I returned

to Greece to work on this problem from 1984-1986, based at the University of Thessaloniki.

This work was possible because of a NATO European Science Exchange Programme fellowship from

the Royal Society and the National Hellenic Research Foundation, and support from the late

Marios Kattoulas and Nikos Loumbourdis of the Department of Zoology. The aim was to provide a

model of the tortoise population including reproduction, the survival and growth of

the relatively elusive juveniles, and survival of adult males and females. In the event it has

taken over 20 years to complete this work at Alyki, with the slow turnover of tortoise

populations and consequent difficulty of measuring survival rates accurately. Further visits

were made in 1988, 1989, 1990, 1998, 1999 and 2001; the British Ecological Society provided

timely assistance from Small Ecological Project Grants in 1990 and 2001.

It was apparent in 1980 that many more males than females were found at Alyki, which could

have been due to either greater activity of males (ths making them easier to find) or to a

real bias in the population sex ratio. Mark-recapture analysis (which takes account of

different activity and ease of finding) of the data from 1980, 1982 and 1983 showed that the

sex ratio was indeed biased, with about two males per female in the

main heath population (Stubbs et al., 1985). I returned

to Greece to work on this problem from 1984-1986, based at the University of Thessaloniki.

This work was possible because of a NATO European Science Exchange Programme fellowship from

the Royal Society and the National Hellenic Research Foundation, and support from the late

Marios Kattoulas and Nikos Loumbourdis of the Department of Zoology. The aim was to provide a

model of the tortoise population including reproduction, the survival and growth of

the relatively elusive juveniles, and survival of adult males and females. In the event it has

taken over 20 years to complete this work at Alyki, with the slow turnover of tortoise

populations and consequent difficulty of measuring survival rates accurately. Further visits

were made in 1988, 1989, 1990, 1998, 1999 and 2001; the British Ecological Society provided

timely assistance from Small Ecological Project Grants in 1990 and 2001.

A possible explanation of the biased sex ratio at Alyki emerged in 1984, when it was observed

that many females had injuries around their tails. These injuries were never seen in males, and

were thought to be caused by courtship attempts. In T. hermanni the male mounts the female

and makes thrusts with his tail around the tail of the female. The tail of the male is much

larger than that of the female, and has a long, sharp spur at its tip; the sharpness is

difficult to quantify, but the tail spur of a male may easily pierce the wall of a standard

beer can. Frequent courtship of this type was thought to damage the females around the tail,

starting with a flesh wound, through exposure of the carapace from beneath, and ending up with

necrosis of the carapace forming a hole above the tail

(Hailey, 1990).

Background information necessary to understand the Alyki population was gathered in the 1980s.

Sexual maturity in males was defined by their courtship behaviour in relation to size and age.

There was a rather sharp start of courtship activity at a size of 13 cm straight carapace length

(SCL), compared to a more gradual increase between 8-11 years (Hailey, 1990); previous studies of

terrapins had shown that maturity was related more to size than to age in chelonians. Male T.

hermanni court immature females so that courtship data cannot be used to define adult size

in females. Studies of egg production using X-rays and oxytocin injection showed that females

at Alyki were mature from a SCL of 15 cm. Clutch size increased with body size both at Alyki and

among other populations of T. hermanni of different body size (Hailey & Loumbourdis,

1988). Experiments with chicken eggs buried to simulate tortoise nests showed that there was

little nest predation at Alyki in 1986 (Hailey & Loumbourdis,

1990).

A possible explanation of the biased sex ratio at Alyki emerged in 1984, when it was observed

that many females had injuries around their tails. These injuries were never seen in males, and

were thought to be caused by courtship attempts. In T. hermanni the male mounts the female

and makes thrusts with his tail around the tail of the female. The tail of the male is much

larger than that of the female, and has a long, sharp spur at its tip; the sharpness is

difficult to quantify, but the tail spur of a male may easily pierce the wall of a standard

beer can. Frequent courtship of this type was thought to damage the females around the tail,

starting with a flesh wound, through exposure of the carapace from beneath, and ending up with

necrosis of the carapace forming a hole above the tail

(Hailey, 1990).

Background information necessary to understand the Alyki population was gathered in the 1980s.

Sexual maturity in males was defined by their courtship behaviour in relation to size and age.

There was a rather sharp start of courtship activity at a size of 13 cm straight carapace length

(SCL), compared to a more gradual increase between 8-11 years (Hailey, 1990); previous studies of

terrapins had shown that maturity was related more to size than to age in chelonians. Male T.

hermanni court immature females so that courtship data cannot be used to define adult size

in females. Studies of egg production using X-rays and oxytocin injection showed that females

at Alyki were mature from a SCL of 15 cm. Clutch size increased with body size both at Alyki and

among other populations of T. hermanni of different body size (Hailey & Loumbourdis,

1988). Experiments with chicken eggs buried to simulate tortoise nests showed that there was

little nest predation at Alyki in 1986 (Hailey & Loumbourdis,

1990).

The sex ratio and population density were found to vary substantially in different parts of the

Alyki site, with very high densities in some areas (Hailey, 1991). Females

in these areas suffered from very high courtship pressure, with inactive females being dug from

refuges by males. Testudo hermanni is a protected species, so experimental manipulation

of population density to increase female mortality is not possible. The variation of density

among different parts of the site provides a natural experiment to test the idea that females

are killed by males. This test depends on the home range of the tortoises; if this is small, then

density can be calculated for small sectors of the site, giving a larger sample size of sub-

populations. Tortoises were followed by thread-trailing. This old technique (Breder, 1927) has

the advantage over radio tracking of showing the exact path moved by an animal, so that both the

home range area and the daily movement distance can be measured. Thread-trailing at Alyki

showed that adult home ranges were rather small, of a few hectares

(Hailey, 1989), so that many sub-populations could be used

for analysis of the sex ratio. Both males and females moved on average about 80 m

day-1, for an annual total distance moved of about 12 km, but with different seasonal

patterns. Subsequent work in France showed that the daily

movement distance was remarkably constant between populations, but the home range area varied

widely.

The sex ratio and population density were found to vary substantially in different parts of the

Alyki site, with very high densities in some areas (Hailey, 1991). Females

in these areas suffered from very high courtship pressure, with inactive females being dug from

refuges by males. Testudo hermanni is a protected species, so experimental manipulation

of population density to increase female mortality is not possible. The variation of density

among different parts of the site provides a natural experiment to test the idea that females

are killed by males. This test depends on the home range of the tortoises; if this is small, then

density can be calculated for small sectors of the site, giving a larger sample size of sub-

populations. Tortoises were followed by thread-trailing. This old technique (Breder, 1927) has

the advantage over radio tracking of showing the exact path moved by an animal, so that both the

home range area and the daily movement distance can be measured. Thread-trailing at Alyki

showed that adult home ranges were rather small, of a few hectares

(Hailey, 1989), so that many sub-populations could be used

for analysis of the sex ratio. Both males and females moved on average about 80 m

day-1, for an annual total distance moved of about 12 km, but with different seasonal

patterns. Subsequent work in France showed that the daily

movement distance was remarkably constant between populations, but the home range area varied

widely.

A comparison of T. hermanni populations in Greece has confirmed that high male:female

sex ratios exist in many populations, and shown that the survival rate

of adult females does decrease at high population density of adult males

(Hailey & Willemsen, 2000). Similar results have been found

among different parts of the Alyki site, with additional effects of density on the body mass

condition of females, and it has been confirmed that the effect on female survival is sufficient

to account for the uneven sex ratios (in preparation). Sex ratios in T. graeca are more

even (Hailey, Wright & Steer, 1988), as expected since this species uses a different type

of courtship behaviour. Male T. graeca butt the female from behind with the front of

the carapace, and their tails are much shorter than those of T. hermanni and without the

sharp terminal spurs (Hailey, 1990). An interesting small population of T. graeca

occurs at Alyki, limited to the open coastal heathland, which numbered

only about 20 adults in the early 1980s

(Hailey, 1988). This population has been growing rapidly,

with a doubling time of 5 years and a rate of increase of about 15% year-1, which can

be regarded as the intrinsic (or maximum, of an unconstrained population in ideal conditions)

rate of increase

(Hailey, 2000a).

The main heath is no longer under threat of development, with a Presidential Decree

safeguarding the area and the local villagers given alternative land for building. There

is increased conservation activity for the bird life, which will also help to preserve the tortoise habitats. Many local people

remain hostile to conservation, however, where this conflicts with building or hunting interests.

The numbers of juvenile tortoises on the main heath had increased by 1990 back to the original

level before the 1980 fire

(Hailey, 2000b).

The tortoises

remain in some danger from increasing development of the salt works, which has become a more

commercial undertaking. Planned increased capacity of the salt works will involve drainage of

the site, possibly decreasing the habitat productivity. A more immediate threat to the

tortoises is an increasing badger population, which has reduced the numbers of juveniles back

to those observed after the fire and ploughing of 1980

(Hailey & Goutner, 2002). Further

experiments with buried chicken eggs showed increasing nest predation, from 17% in 1986, 32%

in 1990, to 68% in 2001. This is, however, a natural danger and reflects the very high

population density that had built up at Alyki. Predation will reduce the population,

but is unlikely to threaten its existence.

The main heath is no longer under threat of development, with a Presidential Decree

safeguarding the area and the local villagers given alternative land for building. There

is increased conservation activity for the bird life, which will also help to preserve the tortoise habitats. Many local people

remain hostile to conservation, however, where this conflicts with building or hunting interests.

The numbers of juvenile tortoises on the main heath had increased by 1990 back to the original

level before the 1980 fire

(Hailey, 2000b).

The tortoises

remain in some danger from increasing development of the salt works, which has become a more

commercial undertaking. Planned increased capacity of the salt works will involve drainage of

the site, possibly decreasing the habitat productivity. A more immediate threat to the

tortoises is an increasing badger population, which has reduced the numbers of juveniles back

to those observed after the fire and ploughing of 1980

(Hailey & Goutner, 2002). Further

experiments with buried chicken eggs showed increasing nest predation, from 17% in 1986, 32%

in 1990, to 68% in 2001. This is, however, a natural danger and reflects the very high

population density that had built up at Alyki. Predation will reduce the population,

but is unlikely to threaten its existence.

The same cannot be said of the salt works heath population of T. hermanni. A

few hundred tortoises lived on the 14 ha strip of land where

the salt works is situated. This was a dense population in the 1980s, characterised by large

numbers of juveniles (Stubbs et al., 1985).

The salt works has developed substantially since

then, with a new evaporation pan, increased areas for salt storage, and dumping of soil from

repair of the evaporation pans on the original habitat. Today the central part of the salt

works heath has been destroyed, with a small area left at either end. Most of the tortoises

which lived in the central area have not been found elsewhere. The evaporation pan pictured,

for example, was in the home range of male no. 1695 (Fig. 2 in Hailey, 1989), which has

disappeared together with other tortoises resident in the same area (in preparation). The

long-term future of tortoises in Greece appears bleak outside of protected areas, with about

0.8% of suitable habitat being destroyed each year (Hailey

& Willemsen, 2003).

The same cannot be said of the salt works heath population of T. hermanni. A

few hundred tortoises lived on the 14 ha strip of land where

the salt works is situated. This was a dense population in the 1980s, characterised by large

numbers of juveniles (Stubbs et al., 1985).

The salt works has developed substantially since

then, with a new evaporation pan, increased areas for salt storage, and dumping of soil from

repair of the evaporation pans on the original habitat. Today the central part of the salt

works heath has been destroyed, with a small area left at either end. Most of the tortoises

which lived in the central area have not been found elsewhere. The evaporation pan pictured,

for example, was in the home range of male no. 1695 (Fig. 2 in Hailey, 1989), which has

disappeared together with other tortoises resident in the same area (in preparation). The

long-term future of tortoises in Greece appears bleak outside of protected areas, with about

0.8% of suitable habitat being destroyed each year (Hailey

& Willemsen, 2003).

Additional references

Breder, R. B. (1927). Turtle trailing: a new technique for studying the life habits of

Testudinata. Zoologica (N.Y.) 9, 231-243.

Stubbs, D., Espin, P. & Mather, R. (1979). Report on expedition to Greece 1979.

University of London Natural History Society, London.

Work at Alyki began well with the site mapped and over 100 tortoises permanently marked by

notching the marginal scutes (Stubbs, Hailey, Pulford & Tyler,

1984). Unknown to us, however, the site was the centre of a planning dispute between

the villagers of Kitros, who collectively owned the land, and the local authorities who

refused proposed industrial development of the area. Faced by further ecological work at the

site, the villagers responded by setting the heathland on fire to reduce its wildlife value,

then using a bulldozer and rotavator to flatten the site.

The expedition remained and marked over 800 tortoises in total, besides describing

the effect of fire and ploughing on tortoises and other wildlife. Analysis of the recapture

data suggested that there had been about 5000 tortoises on the main study area (called the

main heath) before the fire, with population densities of more than 100 tortoises ha-1

in the most favourable habitats

(Stubbs, Hailey, Tyler & Pulford, 1981). Another

expedition to Greece in summer 1982 by

myself, David Stubbs, Elizabeth Pulford and Jan Mata revisited Alyki and marked more than 1000

further tortoises, besides recapturing many marked in 1980.

Work at Alyki began well with the site mapped and over 100 tortoises permanently marked by

notching the marginal scutes (Stubbs, Hailey, Pulford & Tyler,

1984). Unknown to us, however, the site was the centre of a planning dispute between

the villagers of Kitros, who collectively owned the land, and the local authorities who

refused proposed industrial development of the area. Faced by further ecological work at the

site, the villagers responded by setting the heathland on fire to reduce its wildlife value,

then using a bulldozer and rotavator to flatten the site.

The expedition remained and marked over 800 tortoises in total, besides describing

the effect of fire and ploughing on tortoises and other wildlife. Analysis of the recapture

data suggested that there had been about 5000 tortoises on the main study area (called the

main heath) before the fire, with population densities of more than 100 tortoises ha-1

in the most favourable habitats

(Stubbs, Hailey, Tyler & Pulford, 1981). Another

expedition to Greece in summer 1982 by

myself, David Stubbs, Elizabeth Pulford and Jan Mata revisited Alyki and marked more than 1000

further tortoises, besides recapturing many marked in 1980.

David Stubbs also visited Alyki in spring 1983 during his work on

David Stubbs also visited Alyki in spring 1983 during his work on

It was apparent in 1980 that many more males than females were found at Alyki, which could

have been due to either greater activity of males (ths making them easier to find) or to a

real bias in the population sex ratio. Mark-recapture analysis (which takes account of

different activity and ease of finding) of the data from 1980, 1982 and 1983 showed that the

sex ratio was indeed biased, with about two males per female in the

main heath population (

It was apparent in 1980 that many more males than females were found at Alyki, which could

have been due to either greater activity of males (ths making them easier to find) or to a

real bias in the population sex ratio. Mark-recapture analysis (which takes account of

different activity and ease of finding) of the data from 1980, 1982 and 1983 showed that the

sex ratio was indeed biased, with about two males per female in the

main heath population ( A possible explanation of the biased sex ratio at Alyki emerged in 1984, when it was observed

that many females had injuries around their tails. These injuries were never seen in males, and

were thought to be caused by courtship attempts. In T. hermanni the male mounts the female

and makes thrusts with his tail around the tail of the female. The tail of the male is much

larger than that of the female, and has a long, sharp spur at its tip; the sharpness is

difficult to quantify, but the tail spur of a male may easily pierce the wall of a standard

beer can. Frequent courtship of this type was thought to damage the females around the tail,

starting with a flesh wound, through exposure of the carapace from beneath, and ending up with

necrosis of the carapace forming a hole above the tail

(

A possible explanation of the biased sex ratio at Alyki emerged in 1984, when it was observed

that many females had injuries around their tails. These injuries were never seen in males, and

were thought to be caused by courtship attempts. In T. hermanni the male mounts the female

and makes thrusts with his tail around the tail of the female. The tail of the male is much

larger than that of the female, and has a long, sharp spur at its tip; the sharpness is

difficult to quantify, but the tail spur of a male may easily pierce the wall of a standard

beer can. Frequent courtship of this type was thought to damage the females around the tail,

starting with a flesh wound, through exposure of the carapace from beneath, and ending up with

necrosis of the carapace forming a hole above the tail

( The sex ratio and population density were found to vary substantially in different parts of the

Alyki site, with very high densities in some areas (Hailey, 1991). Females

in these areas suffered from very high courtship pressure, with inactive females being dug from

refuges by males. Testudo hermanni is a protected species, so experimental manipulation

of population density to increase female mortality is not possible. The variation of density

among different parts of the site provides a natural experiment to test the idea that females

are killed by males. This test depends on the home range of the tortoises; if this is small, then

density can be calculated for small sectors of the site, giving a larger sample size of sub-

populations. Tortoises were followed by thread-trailing. This old technique (Breder, 1927) has

the advantage over radio tracking of showing the exact path moved by an animal, so that both the

home range area and the daily movement distance can be measured. Thread-trailing at Alyki

showed that adult home ranges were rather small, of a few hectares

(

The sex ratio and population density were found to vary substantially in different parts of the

Alyki site, with very high densities in some areas (Hailey, 1991). Females

in these areas suffered from very high courtship pressure, with inactive females being dug from

refuges by males. Testudo hermanni is a protected species, so experimental manipulation

of population density to increase female mortality is not possible. The variation of density

among different parts of the site provides a natural experiment to test the idea that females

are killed by males. This test depends on the home range of the tortoises; if this is small, then

density can be calculated for small sectors of the site, giving a larger sample size of sub-

populations. Tortoises were followed by thread-trailing. This old technique (Breder, 1927) has

the advantage over radio tracking of showing the exact path moved by an animal, so that both the

home range area and the daily movement distance can be measured. Thread-trailing at Alyki

showed that adult home ranges were rather small, of a few hectares

( The main heath is no longer under threat of development, with a Presidential Decree

safeguarding the area and the local villagers given alternative land for building. There

is increased conservation activity for the bird life, which will also help to preserve the tortoise habitats. Many local people

remain hostile to conservation, however, where this conflicts with building or hunting interests.

The numbers of juvenile tortoises on the main heath had increased by 1990 back to the original

level before the 1980 fire

(

The main heath is no longer under threat of development, with a Presidential Decree

safeguarding the area and the local villagers given alternative land for building. There

is increased conservation activity for the bird life, which will also help to preserve the tortoise habitats. Many local people

remain hostile to conservation, however, where this conflicts with building or hunting interests.

The numbers of juvenile tortoises on the main heath had increased by 1990 back to the original

level before the 1980 fire

( The same cannot be said of the salt works heath population of T. hermanni. A

few hundred tortoises lived on the 14 ha strip of land where

the salt works is situated. This was a dense population in the 1980s, characterised by large

numbers of juveniles (

The same cannot be said of the salt works heath population of T. hermanni. A

few hundred tortoises lived on the 14 ha strip of land where

the salt works is situated. This was a dense population in the 1980s, characterised by large

numbers of juveniles (