Physiological ecology is the combination of physiology and ecology, but in what sense ?

Most physiological ecology in the early 1980s, and still today, concerns ecologists

investigating the influence of the observed physiology of an organism on its ecology and

behaviour. The

complementary approach of ecophysiology mostly concerns physiologists investigating

the physiological adaptations of an organism

to its observed ecology and environment. Paradoxically, both ecologists and physiologists

thus appear to view the other discipline as being fixed and so more fundamental. However, both

the ecology and the

physiology of an organism are subject to selection, and ultimately physiological

ecology should examine the

coadaptation of the two sets of variables. The overall aim of my Ph.D. research (Hailey, 1984),

supervised by Peter Davies, was to examine the

coadaptation of thermal biology and the physiology of performance with activity and

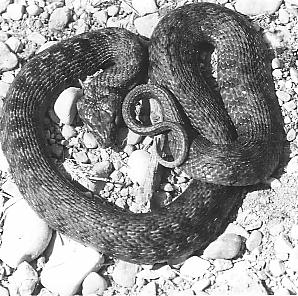

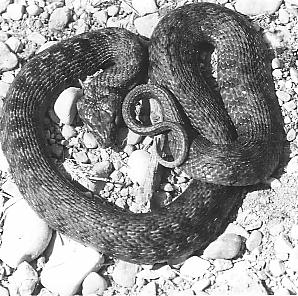

foraging behaviour in an ectotherm. The species

chosen was the viperine water snake Natrix maura, named for its mimicry of European

vipers Vipera in both appearance, coloration and defensive behaviour. Preliminary

studies (Davies, Patterson & Bennett, 1980; Patterson & Davies, 1982) had examined the resting

metabolism and body temperatures of this species, and identified a dense population in the

river Jalon near Calpe in eastern Spain (Patterson & Davies, 1977).

The project required fieldwork in Spain and extensive laboratory studies to investigate

the thermal biology of this species and of the related grass snake, Natrix natrix. Body

temperature was shown to affect aerobic metabolism, both at rest and during maximal activity,

anaerobic metabolism (lactate production) during intense activity, burst speed, and endurance

(Hailey & Davies, 1986a). Snakes were also more likely to use

static defensive behaviour (the viperine display) at low body temperatures, presumably

because they were less able to escape as a result of lower physiological performance.

Physiological ecology is the combination of physiology and ecology, but in what sense ?

Most physiological ecology in the early 1980s, and still today, concerns ecologists

investigating the influence of the observed physiology of an organism on its ecology and

behaviour. The

complementary approach of ecophysiology mostly concerns physiologists investigating

the physiological adaptations of an organism

to its observed ecology and environment. Paradoxically, both ecologists and physiologists

thus appear to view the other discipline as being fixed and so more fundamental. However, both

the ecology and the

physiology of an organism are subject to selection, and ultimately physiological

ecology should examine the

coadaptation of the two sets of variables. The overall aim of my Ph.D. research (Hailey, 1984),

supervised by Peter Davies, was to examine the

coadaptation of thermal biology and the physiology of performance with activity and

foraging behaviour in an ectotherm. The species

chosen was the viperine water snake Natrix maura, named for its mimicry of European

vipers Vipera in both appearance, coloration and defensive behaviour. Preliminary

studies (Davies, Patterson & Bennett, 1980; Patterson & Davies, 1982) had examined the resting

metabolism and body temperatures of this species, and identified a dense population in the

river Jalon near Calpe in eastern Spain (Patterson & Davies, 1977).

The project required fieldwork in Spain and extensive laboratory studies to investigate

the thermal biology of this species and of the related grass snake, Natrix natrix. Body

temperature was shown to affect aerobic metabolism, both at rest and during maximal activity,

anaerobic metabolism (lactate production) during intense activity, burst speed, and endurance

(Hailey & Davies, 1986a). Snakes were also more likely to use

static defensive behaviour (the viperine display) at low body temperatures, presumably

because they were less able to escape as a result of lower physiological performance.

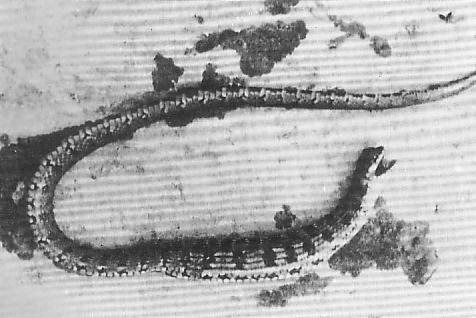

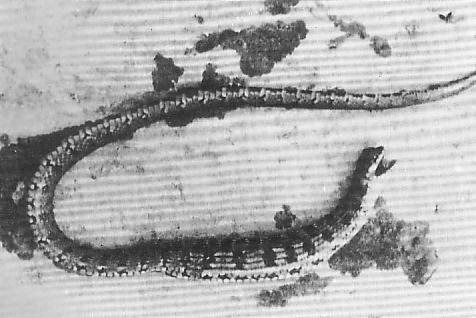

Fieldwork involved a mark-recapture study of N. maura in the Jalon river, in which about

1700 individuals were captured and released from 1981-1983. Snakes were marked by

clipping the ventral scutes, but they were also recognised by a form of "fingerprinting" using

natural markings on the ventral scales (Hailey & Davies, 1985).

Each individual was photographed in a perspex press each

time it was captured, and a total of 2283 such photographs were available. The negatives were viewed

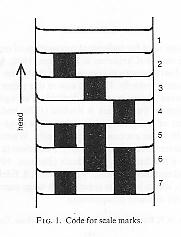

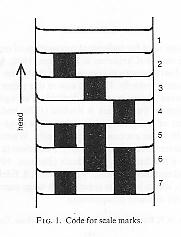

on a back-projector screen and the patterns were coded by hand, with the mark on each scale

corresponding to one of seven digits from 1 (no mark) to 7 (both right and left marks).

The pattern made an array of a 5-digit identifier and up to 155 scales, thus filling two rows

of the 80-column data format then in use. The average was about 150 scales per snake, so spare array

elements were left as 0. The pattern shown, the original capture of snake #11, was coded as:

Fieldwork involved a mark-recapture study of N. maura in the Jalon river, in which about

1700 individuals were captured and released from 1981-1983. Snakes were marked by

clipping the ventral scutes, but they were also recognised by a form of "fingerprinting" using

natural markings on the ventral scales (Hailey & Davies, 1985).

Each individual was photographed in a perspex press each

time it was captured, and a total of 2283 such photographs were available. The negatives were viewed

on a back-projector screen and the patterns were coded by hand, with the mark on each scale

corresponding to one of seven digits from 1 (no mark) to 7 (both right and left marks).

The pattern made an array of a 5-digit identifier and up to 155 scales, thus filling two rows

of the 80-column data format then in use. The average was about 150 scales per snake, so spare array

elements were left as 0. The pattern shown, the original capture of snake #11, was coded as:

00011111113113113111111111211711711233712217365165177377172472472422442442772243

24124424713733731743742242242172421421771771721422421421741724724214241171000000

Recognition of Natrix by natural markings of the ventral scales had been proposed many

years ago (Carlstrom & Edelstam, 1946). My main innovation was to compare the patterns by

computer, thus permitting the system to be used in a large population; this would be

impossible to do by comparing photographs directly since the number of comparisons

increases exponentially with the number of individuals. If each pattern is

compared with all those recorded previously in order to recognise recaptures, then n captures

involve n(n-1)/2 one-way comparisons; more than 2.6 million comparisons for the

2283 patterns recorded here. Even if each comparison took only 10 seconds, the total would be

more than 7000 hours.

Patterns were compared using a FORTRAN program which summed the absolute (unsigned) difference

between the codes in each scale position, giving an index of dissimilarity; an exact match

would give a

score of 0, up to a theoretical maximum of about 930 (comparing an unmarked snake with one with

complete double markings). The most serious error in coding was starting from the wrong

position, as the first ventral scales, on the neck, are small and easily mistaken in a photograph.

The new pattern was thus moved past the earlier one in a series of 9 steps, from -4 to +4

positions, and the dissimilarity index calculated at each step; the lowest of these, the minimum

dissimilarity index, was used as the final result. There was sufficient information content

to give odds of 1000:1 against duplication in a population of 1020 snakes, even after

taking non-randomness within the patterns into account. The method was found to be

99% effective, with only some patterns from poor photographs not being recognised. In fact,

several recaptures which were recorded wrongly by scale clips were identified correctly

by patterns.

Recognition of Natrix by natural markings of the ventral scales had been proposed many

years ago (Carlstrom & Edelstam, 1946). My main innovation was to compare the patterns by

computer, thus permitting the system to be used in a large population; this would be

impossible to do by comparing photographs directly since the number of comparisons

increases exponentially with the number of individuals. If each pattern is

compared with all those recorded previously in order to recognise recaptures, then n captures

involve n(n-1)/2 one-way comparisons; more than 2.6 million comparisons for the

2283 patterns recorded here. Even if each comparison took only 10 seconds, the total would be

more than 7000 hours.

Patterns were compared using a FORTRAN program which summed the absolute (unsigned) difference

between the codes in each scale position, giving an index of dissimilarity; an exact match

would give a

score of 0, up to a theoretical maximum of about 930 (comparing an unmarked snake with one with

complete double markings). The most serious error in coding was starting from the wrong

position, as the first ventral scales, on the neck, are small and easily mistaken in a photograph.

The new pattern was thus moved past the earlier one in a series of 9 steps, from -4 to +4

positions, and the dissimilarity index calculated at each step; the lowest of these, the minimum

dissimilarity index, was used as the final result. There was sufficient information content

to give odds of 1000:1 against duplication in a population of 1020 snakes, even after

taking non-randomness within the patterns into account. The method was found to be

99% effective, with only some patterns from poor photographs not being recognised. In fact,

several recaptures which were recorded wrongly by scale clips were identified correctly

by patterns.

Mark-recapture analysis showed that the survival rate of snakes in the river Jalon was about 65%

year-1 in both sexes, with some males migrating into peripheral areas where few

females were found (Hailey & Davies, 1987d). Viperine snakes

were active at all times of the day and night, and mostly used sentinel predation. This is an

extreme form of sit-and-wait foraging, whereby the snake made strikes from its resting

position in aquatic vegetation or on the bottom, rather than rushing out to ambush prey. The main

prey were fish, with some frogs taken by the larger snakes; juveniles were more active predators

of tadpoles and worms. Larger snakes took larger fish, but the relative prey mass was independent

of snake size (Hailey & Davies, 1986c).

Mark-recapture analysis showed that the survival rate of snakes in the river Jalon was about 65%

year-1 in both sexes, with some males migrating into peripheral areas where few

females were found (Hailey & Davies, 1987d). Viperine snakes

were active at all times of the day and night, and mostly used sentinel predation. This is an

extreme form of sit-and-wait foraging, whereby the snake made strikes from its resting

position in aquatic vegetation or on the bottom, rather than rushing out to ambush prey. The main

prey were fish, with some frogs taken by the larger snakes; juveniles were more active predators

of tadpoles and worms. Larger snakes took larger fish, but the relative prey mass was independent

of snake size (Hailey & Davies, 1986c).

Selection of fish was

investigated in the laboratory. Viperine snakes selected the largest fish available, up to the maximum

size that they could ingest (Hailey & Davies, 1986d), rather

than those giving the maximum intake per unit handling time. This is the optimal pattern when

selecting prey from groups when only one individual may be captured from each group, as the others

escape while this is being handled. In fact snakes often captured fish rather too large for them

to ingest, probably because estimation of size is uncertain and it would be more costly to leave

a fish that could have been ingested, than to spend some time struggling with an excessive fish

before giving up. There would be some danger from fish too large to ingest but just large enough

to block the throat; one snake was found choked on a fish of 66% relative prey mass.

Reproductive characteristics of N. maura included female larger than male sexual size

dimorphism and females becoming more heavy-bodied than males at maturity, probably to

accomodate eggs. Clutch size increased with female size during growth. Combining data on

reproduction and survival showed that current and future reproduction increased in parallel, and

reproductive effort was constant during adult growth of females. There was evidence of multiple

mating in females, and a long mating season, from sperm in dried cloacal smears

(Hailey & Davies, 1987b).

Field work also studied the thermal relations of N. maura. Snakes were active in water

down to 14oC, between March and October. Body temperatures of snakes in water

were close to water temperatures (Hailey, Davies & Pulford, 1982).

Snakes were also often seen basking, when their body temperatures were relatively independent of

ambient temperature, indicating successful thermoregulation. Snakes basked for long periods,

much longer than would be required simply to reach a high body temperature. The benefit of

these long basking periods was possibly to increase the rate of digestion. Studies with snakes

feeding on fish in the laboratory

showed that the rate of digestion was strongly influenced by temperature. The efficiency

of digestion was affected much less, down to 15oC; below this temperature digestion was

incomplete and the fish were regurgitated. Oxygen consumption increased during

digestion, which is termed the specific dynamic action or SDA, and this increase accounted for

about 28% of the energy

in the food. Temperature affected the time course of the SDA, which was shorter at high temperatures,

but not the total energy cost of the SDA. Basking did have an energy cost, however, as the resting metabolic rate

increases at high temperature. It was calculated that a snake raising its body temperature

from 15oC to 25o during the digestion of a fish would lose about 4% of the

energy of the food due to increased resting metabolism

(Hailey & Davies, 1987c).

Field work also studied the thermal relations of N. maura. Snakes were active in water

down to 14oC, between March and October. Body temperatures of snakes in water

were close to water temperatures (Hailey, Davies & Pulford, 1982).

Snakes were also often seen basking, when their body temperatures were relatively independent of

ambient temperature, indicating successful thermoregulation. Snakes basked for long periods,

much longer than would be required simply to reach a high body temperature. The benefit of

these long basking periods was possibly to increase the rate of digestion. Studies with snakes

feeding on fish in the laboratory

showed that the rate of digestion was strongly influenced by temperature. The efficiency

of digestion was affected much less, down to 15oC; below this temperature digestion was

incomplete and the fish were regurgitated. Oxygen consumption increased during

digestion, which is termed the specific dynamic action or SDA, and this increase accounted for

about 28% of the energy

in the food. Temperature affected the time course of the SDA, which was shorter at high temperatures,

but not the total energy cost of the SDA. Basking did have an energy cost, however, as the resting metabolic rate

increases at high temperature. It was calculated that a snake raising its body temperature

from 15oC to 25o during the digestion of a fish would lose about 4% of the

energy of the food due to increased resting metabolism

(Hailey & Davies, 1987c).

Digestion of a large prey such as a fish takes from several hours to a few days. This

explains why snakes bask for much longer than required

simply to raise body temperature; they need to maintain high body temperature as well, throughout

the course of digestion. The usual basking period of reptiles is much shorter;

most lizards for example bask for a few minutes to warm up, then move away to feed, until their

body temperature falls and they need to bask again. This produces the typical behaviour pattern

known as shuttling heliothermy, where lizards move into and out of the sun. Recognition of these

two major patterns of basking is easier if they are appropriately named, and the terms r and K

thermoregulation were suggested

(Hailey & Davies, 1987a). The rationale behind these terms is that

heating curves have a logistic component, the rate of increase decreasing as body temperature

approaches the equilibrium for the conditions

(Hailey, 1982). By analogy with the r-K spectrum of life

history strategies, short-term r-thermoregulators should maximise the rate of heating (r)

whereas long-term K-thermoregulators should maintain a suitable equilibrium temperature (K).

The temperature actually maintained (K*) may not be the highest possible in the conditions (K)

if this would be too high. Basking N. maura did indeed move partly into shade in hot

weather, and basked with only part of the body exposed to the sun; this would be inexplicable

in an r-thermoregulator seeking to maximise the rate of heating. K-thermoregulation is shown by

many other reptiles, including the Moorish gecko

which feeds at night but basks during the day; interestingly the other common European

gecko Hemidactylus turcicus never basks. r-thermoregulation is always by basking, but

K-thermoregulation is often by choice of a warm microenvironment such as the inner surface

of loose bark or the underside of a thin rock.

Digestion of a large prey such as a fish takes from several hours to a few days. This

explains why snakes bask for much longer than required

simply to raise body temperature; they need to maintain high body temperature as well, throughout

the course of digestion. The usual basking period of reptiles is much shorter;

most lizards for example bask for a few minutes to warm up, then move away to feed, until their

body temperature falls and they need to bask again. This produces the typical behaviour pattern

known as shuttling heliothermy, where lizards move into and out of the sun. Recognition of these

two major patterns of basking is easier if they are appropriately named, and the terms r and K

thermoregulation were suggested

(Hailey & Davies, 1987a). The rationale behind these terms is that

heating curves have a logistic component, the rate of increase decreasing as body temperature

approaches the equilibrium for the conditions

(Hailey, 1982). By analogy with the r-K spectrum of life

history strategies, short-term r-thermoregulators should maximise the rate of heating (r)

whereas long-term K-thermoregulators should maintain a suitable equilibrium temperature (K).

The temperature actually maintained (K*) may not be the highest possible in the conditions (K)

if this would be too high. Basking N. maura did indeed move partly into shade in hot

weather, and basked with only part of the body exposed to the sun; this would be inexplicable

in an r-thermoregulator seeking to maximise the rate of heating. K-thermoregulation is shown by

many other reptiles, including the Moorish gecko

which feeds at night but basks during the day; interestingly the other common European

gecko Hemidactylus turcicus never basks. r-thermoregulation is always by basking, but

K-thermoregulation is often by choice of a warm microenvironment such as the inner surface

of loose bark or the underside of a thin rock.

Earlier work had compared the resting metabolism of N. maura from Spain with that of

the grass snake Natrix natrix from England. Metabolic rates of the grass snake were

elevated above those of N. maura at the same temperature, which would be expected if

grass snakes had lower body temperatures in the cooler climate of England (Davies, Patterson &

Bennett, 1981). The two species also probably differ in lifestyle, however, with the grass snake

a more active predator of amphibians, and this would also be expected to cause elevated

metabolic rates to give greater scope for activity. The foraging behaviour of the grass snake

was also studied in Spain; this was a diurnally active widely-foraging predator of frogs,

compared to N. maura the sentinel predator of fish active by day and night. Body

temperatures of grass snakes were higher and less variable than those of viperine snakes during

activity. Metabolic rates of viperine snakes and grass snakes

from both southern Europe and England were also measured. The southern grass snakes were

actually N. natrix persa from Greece, which ate fish readily and could be maintained in

captivity more easily than

Spanish snakes which required frogs. This three way comparison was expected to show:

1) Grass snakes from England having higher metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an

adaptation to the cooler climate. 2) Viperine snakes having lower and less temperature-sensitive

metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an adaptation to lower activity during sentinel

foraging and to more variable

body temperatures during activity at night and in water. 3) That these patterns occurred

for metabolism during activity as well as for resting metabolism; the latter is an energy cost,

the benefit of high metabolic rate comes from activity. All three predictions were verified

(Hailey & Davies, 1986b).

Earlier work had compared the resting metabolism of N. maura from Spain with that of

the grass snake Natrix natrix from England. Metabolic rates of the grass snake were

elevated above those of N. maura at the same temperature, which would be expected if

grass snakes had lower body temperatures in the cooler climate of England (Davies, Patterson &

Bennett, 1981). The two species also probably differ in lifestyle, however, with the grass snake

a more active predator of amphibians, and this would also be expected to cause elevated

metabolic rates to give greater scope for activity. The foraging behaviour of the grass snake

was also studied in Spain; this was a diurnally active widely-foraging predator of frogs,

compared to N. maura the sentinel predator of fish active by day and night. Body

temperatures of grass snakes were higher and less variable than those of viperine snakes during

activity. Metabolic rates of viperine snakes and grass snakes

from both southern Europe and England were also measured. The southern grass snakes were

actually N. natrix persa from Greece, which ate fish readily and could be maintained in

captivity more easily than

Spanish snakes which required frogs. This three way comparison was expected to show:

1) Grass snakes from England having higher metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an

adaptation to the cooler climate. 2) Viperine snakes having lower and less temperature-sensitive

metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an adaptation to lower activity during sentinel

foraging and to more variable

body temperatures during activity at night and in water. 3) That these patterns occurred

for metabolism during activity as well as for resting metabolism; the latter is an energy cost,

the benefit of high metabolic rate comes from activity. All three predictions were verified

(Hailey & Davies, 1986b).

Field and laboratory data were finally used in a model to examine the coadaptation of

ecology and physiology. The basis of the model was: 1) Maximum aerobic metabolic rate

determines the level of sustainable activity possible by the snake. This is related to

resting metabolic rate by a constant factorial scope; the maximum rate is ten times the

resting rate. This pattern holds for the comparison of reptiles with mammals,

and among different types of reptile

(Loumbourdis & Hailey, 1985). 2) Foraging activity

requires a certain aerobic scope; this is the difference between maximum and resting

metabolic rates, in other words the metabolism that is above the maintenance level and thus

available for activity .

The required scope is that measured at 14oC, the minimum

temperature for activity in the field. 3) Foraging activity is in water, and is thus

constrained to be at water temperature. Body temperatures can be raised by basking, but as this

is usually to increase the rate of digestion, the extra metabolic cost involved can be viewed

as a simple "tax" on the food digested and so ignored as a cost of resting metabolic rate.

4) Water temperatures are fixed by the environment. The level and the temperature-sensitivity

(measured as the temperature quotient, Q10) of

resting metabolism are thus the only independent variables in the model: maximum metabolic rate

is calculated from the resting rate through the fixed factorial scope; the metabolic

threshold for activity occurs where the calculated aerobic scope equals that observed at

14oC; the temperature at which this occurs determines the possible activity times

and the length of the active season; integration of the resting metabolic rate-temperature curve

with the annual distribution of water temperature determines the annual maintenance cost of

metabolism. This relatively simple model provides a useful framework to view coadaptation of

ecology and physiology. The results in N. maura showed that the observed combination of

metabolism, body temperature and activity was close to the maximum possible efficiency, in

terms of the

activity season allowed per unit of metabolic cost (Hailey & Davies,

1988).

These studies benefitted greatly from discussion in laboratory and field with Peter Davies,

and with the other postgraduate students in his energetics research group, Abdussalam, Abdul

Wahab Al Hakim and Malcolm McClelland. The work was supported by a studentship from the Natural

Environment Research Council (NERC).

Additional references

Carstrom, D. & Edelstam, C. (1946). Methods of marking reptiles for identification after

re-capture. Nature 158, 748-749.

Davies, P. M. C., Patterson, J. W. & Bennett, E. L. (1980). The thermal ecology, physiology

and behaviour of the viperine snake, Natrix maura: some preliminary observations. In

Coborn, J. (Ed.), Proceedings of the European Herpetological Symposium, p107-116.

Cotswold Wild Life Park.

Davies, P. M. C., Patterson, J. W. & Bennett, E. L. (1981). Metabolic coping strategies in

cold tolerant reptiles. J. Therm. Biol. 6, 321-330.

Hailey, A. (1984). Ecology of the viperine snake, Natrix maura. Unpublished Ph.D.

thesis, University of Nottingham.

Patterson, J. W. & Davies, P. M. C. (1977). Notes on the herpetology of the Costa Blanca in

spring. Brit. J. Herpetol. 5, 685-686.

Patterson, J. W. and Davies, P. M. C. (1982). Predatory behaviour and temperature relations

in the snake Natrix maura. Copeia 1982, 472-474.

Physiological ecology is the combination of physiology and ecology, but in what sense ?

Most physiological ecology in the early 1980s, and still today, concerns ecologists

investigating the influence of the observed physiology of an organism on its ecology and

behaviour. The

complementary approach of ecophysiology mostly concerns physiologists investigating

the physiological adaptations of an organism

to its observed ecology and environment. Paradoxically, both ecologists and physiologists

thus appear to view the other discipline as being fixed and so more fundamental. However, both

the ecology and the

physiology of an organism are subject to selection, and ultimately physiological

ecology should examine the

coadaptation of the two sets of variables. The overall aim of my Ph.D. research (Hailey, 1984),

supervised by Peter Davies, was to examine the

coadaptation of thermal biology and the physiology of performance with activity and

foraging behaviour in an ectotherm. The species

chosen was the viperine water snake Natrix maura, named for its mimicry of European

vipers Vipera in both appearance, coloration and defensive behaviour. Preliminary

studies (Davies, Patterson & Bennett, 1980; Patterson & Davies, 1982) had examined the resting

metabolism and body temperatures of this species, and identified a dense population in the

river Jalon near Calpe in eastern Spain (Patterson & Davies, 1977).

The project required fieldwork in Spain and extensive laboratory studies to investigate

the thermal biology of this species and of the related grass snake, Natrix natrix. Body

temperature was shown to affect aerobic metabolism, both at rest and during maximal activity,

anaerobic metabolism (lactate production) during intense activity, burst speed, and endurance

(Hailey & Davies, 1986a). Snakes were also more likely to use

static defensive behaviour (the viperine display) at low body temperatures, presumably

because they were less able to escape as a result of lower physiological performance.

Physiological ecology is the combination of physiology and ecology, but in what sense ?

Most physiological ecology in the early 1980s, and still today, concerns ecologists

investigating the influence of the observed physiology of an organism on its ecology and

behaviour. The

complementary approach of ecophysiology mostly concerns physiologists investigating

the physiological adaptations of an organism

to its observed ecology and environment. Paradoxically, both ecologists and physiologists

thus appear to view the other discipline as being fixed and so more fundamental. However, both

the ecology and the

physiology of an organism are subject to selection, and ultimately physiological

ecology should examine the

coadaptation of the two sets of variables. The overall aim of my Ph.D. research (Hailey, 1984),

supervised by Peter Davies, was to examine the

coadaptation of thermal biology and the physiology of performance with activity and

foraging behaviour in an ectotherm. The species

chosen was the viperine water snake Natrix maura, named for its mimicry of European

vipers Vipera in both appearance, coloration and defensive behaviour. Preliminary

studies (Davies, Patterson & Bennett, 1980; Patterson & Davies, 1982) had examined the resting

metabolism and body temperatures of this species, and identified a dense population in the

river Jalon near Calpe in eastern Spain (Patterson & Davies, 1977).

The project required fieldwork in Spain and extensive laboratory studies to investigate

the thermal biology of this species and of the related grass snake, Natrix natrix. Body

temperature was shown to affect aerobic metabolism, both at rest and during maximal activity,

anaerobic metabolism (lactate production) during intense activity, burst speed, and endurance

(Hailey & Davies, 1986a). Snakes were also more likely to use

static defensive behaviour (the viperine display) at low body temperatures, presumably

because they were less able to escape as a result of lower physiological performance. Fieldwork involved a mark-recapture study of N. maura in the Jalon river, in which about

1700 individuals were captured and released from 1981-1983. Snakes were marked by

clipping the ventral scutes, but they were also recognised by a form of "fingerprinting" using

natural markings on the ventral scales (

Fieldwork involved a mark-recapture study of N. maura in the Jalon river, in which about

1700 individuals were captured and released from 1981-1983. Snakes were marked by

clipping the ventral scutes, but they were also recognised by a form of "fingerprinting" using

natural markings on the ventral scales ( Recognition of Natrix by natural markings of the ventral scales had been proposed many

years ago (Carlstrom & Edelstam, 1946). My main innovation was to compare the patterns by

computer, thus permitting the system to be used in a large population; this would be

impossible to do by comparing photographs directly since the number of comparisons

increases exponentially with the number of individuals. If each pattern is

compared with all those recorded previously in order to recognise recaptures, then n captures

involve n(n-1)/2 one-way comparisons; more than 2.6 million comparisons for the

2283 patterns recorded here. Even if each comparison took only 10 seconds, the total would be

more than 7000 hours.

Patterns were compared using a FORTRAN program which summed the absolute (unsigned) difference

between the codes in each scale position, giving an index of dissimilarity; an exact match

would give a

score of 0, up to a theoretical maximum of about 930 (comparing an unmarked snake with one with

complete double markings). The most serious error in coding was starting from the wrong

position, as the first ventral scales, on the neck, are small and easily mistaken in a photograph.

The new pattern was thus moved past the earlier one in a series of 9 steps, from -4 to +4

positions, and the dissimilarity index calculated at each step; the lowest of these, the minimum

dissimilarity index, was used as the final result. There was sufficient information content

to give odds of 1000:1 against duplication in a population of 1020 snakes, even after

taking non-randomness within the patterns into account. The method was found to be

99% effective, with only some patterns from poor photographs not being recognised. In fact,

several recaptures which were recorded wrongly by scale clips were identified correctly

by patterns.

Recognition of Natrix by natural markings of the ventral scales had been proposed many

years ago (Carlstrom & Edelstam, 1946). My main innovation was to compare the patterns by

computer, thus permitting the system to be used in a large population; this would be

impossible to do by comparing photographs directly since the number of comparisons

increases exponentially with the number of individuals. If each pattern is

compared with all those recorded previously in order to recognise recaptures, then n captures

involve n(n-1)/2 one-way comparisons; more than 2.6 million comparisons for the

2283 patterns recorded here. Even if each comparison took only 10 seconds, the total would be

more than 7000 hours.

Patterns were compared using a FORTRAN program which summed the absolute (unsigned) difference

between the codes in each scale position, giving an index of dissimilarity; an exact match

would give a

score of 0, up to a theoretical maximum of about 930 (comparing an unmarked snake with one with

complete double markings). The most serious error in coding was starting from the wrong

position, as the first ventral scales, on the neck, are small and easily mistaken in a photograph.

The new pattern was thus moved past the earlier one in a series of 9 steps, from -4 to +4

positions, and the dissimilarity index calculated at each step; the lowest of these, the minimum

dissimilarity index, was used as the final result. There was sufficient information content

to give odds of 1000:1 against duplication in a population of 1020 snakes, even after

taking non-randomness within the patterns into account. The method was found to be

99% effective, with only some patterns from poor photographs not being recognised. In fact,

several recaptures which were recorded wrongly by scale clips were identified correctly

by patterns.

Mark-recapture analysis showed that the survival rate of snakes in the river Jalon was about 65%

year-1 in both sexes, with some males migrating into peripheral areas where few

females were found (

Mark-recapture analysis showed that the survival rate of snakes in the river Jalon was about 65%

year-1 in both sexes, with some males migrating into peripheral areas where few

females were found ( Field work also studied the thermal relations of N. maura. Snakes were active in water

down to 14oC, between March and October. Body temperatures of snakes in water

were close to water temperatures (

Field work also studied the thermal relations of N. maura. Snakes were active in water

down to 14oC, between March and October. Body temperatures of snakes in water

were close to water temperatures ( Digestion of a large prey such as a fish takes from several hours to a few days. This

explains why snakes bask for much longer than required

simply to raise body temperature; they need to maintain high body temperature as well, throughout

the course of digestion. The usual basking period of reptiles is much shorter;

most lizards for example bask for a few minutes to warm up, then move away to feed, until their

body temperature falls and they need to bask again. This produces the typical behaviour pattern

known as shuttling heliothermy, where lizards move into and out of the sun. Recognition of these

two major patterns of basking is easier if they are appropriately named, and the terms r and K

thermoregulation were suggested

(

Digestion of a large prey such as a fish takes from several hours to a few days. This

explains why snakes bask for much longer than required

simply to raise body temperature; they need to maintain high body temperature as well, throughout

the course of digestion. The usual basking period of reptiles is much shorter;

most lizards for example bask for a few minutes to warm up, then move away to feed, until their

body temperature falls and they need to bask again. This produces the typical behaviour pattern

known as shuttling heliothermy, where lizards move into and out of the sun. Recognition of these

two major patterns of basking is easier if they are appropriately named, and the terms r and K

thermoregulation were suggested

( Earlier work had compared the resting metabolism of N. maura from Spain with that of

the grass snake Natrix natrix from England. Metabolic rates of the grass snake were

elevated above those of N. maura at the same temperature, which would be expected if

grass snakes had lower body temperatures in the cooler climate of England (Davies, Patterson &

Bennett, 1981). The two species also probably differ in lifestyle, however, with the grass snake

a more active predator of amphibians, and this would also be expected to cause elevated

metabolic rates to give greater scope for activity. The foraging behaviour of the grass snake

was also studied in Spain; this was a diurnally active widely-foraging predator of frogs,

compared to N. maura the sentinel predator of fish active by day and night. Body

temperatures of grass snakes were higher and less variable than those of viperine snakes during

activity. Metabolic rates of viperine snakes and grass snakes

from both southern Europe and England were also measured. The southern grass snakes were

actually N. natrix persa from Greece, which ate fish readily and could be maintained in

captivity more easily than

Spanish snakes which required frogs. This three way comparison was expected to show:

1) Grass snakes from England having higher metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an

adaptation to the cooler climate. 2) Viperine snakes having lower and less temperature-sensitive

metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an adaptation to lower activity during sentinel

foraging and to more variable

body temperatures during activity at night and in water. 3) That these patterns occurred

for metabolism during activity as well as for resting metabolism; the latter is an energy cost,

the benefit of high metabolic rate comes from activity. All three predictions were verified

(

Earlier work had compared the resting metabolism of N. maura from Spain with that of

the grass snake Natrix natrix from England. Metabolic rates of the grass snake were

elevated above those of N. maura at the same temperature, which would be expected if

grass snakes had lower body temperatures in the cooler climate of England (Davies, Patterson &

Bennett, 1981). The two species also probably differ in lifestyle, however, with the grass snake

a more active predator of amphibians, and this would also be expected to cause elevated

metabolic rates to give greater scope for activity. The foraging behaviour of the grass snake

was also studied in Spain; this was a diurnally active widely-foraging predator of frogs,

compared to N. maura the sentinel predator of fish active by day and night. Body

temperatures of grass snakes were higher and less variable than those of viperine snakes during

activity. Metabolic rates of viperine snakes and grass snakes

from both southern Europe and England were also measured. The southern grass snakes were

actually N. natrix persa from Greece, which ate fish readily and could be maintained in

captivity more easily than

Spanish snakes which required frogs. This three way comparison was expected to show:

1) Grass snakes from England having higher metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an

adaptation to the cooler climate. 2) Viperine snakes having lower and less temperature-sensitive

metabolic rates than southern grass snakes, an adaptation to lower activity during sentinel

foraging and to more variable

body temperatures during activity at night and in water. 3) That these patterns occurred

for metabolism during activity as well as for resting metabolism; the latter is an energy cost,

the benefit of high metabolic rate comes from activity. All three predictions were verified

(